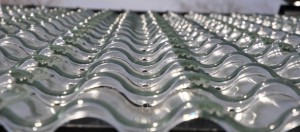

The sea-wall built by members of the Philippines Homeless People’s Federation in Davao with a loan from the the Asian Coalition for Community Action. The loan encouraged the government to extend the wall further. Credit: ACHR

The sea-wall built by members of the Philippines Homeless People’s Federation in Davao with a loan from the the Asian Coalition for Community Action. The loan encouraged the government to extend the wall further. Credit: ACHR

1: Climate change adaptation needs to support change on the ground

This includes working with those most at risk from storms, floods and heat waves and other hazards associated with climate change. Somsook Boonyabancha from the Asian Coalition for Housing Rights gave many examples of risk-reducing initiatives in informal settlements. Since 2009, the Asian Coalition for Community Action (ACCA) has supported over 1,000 community initiatives in 168 cities in 19 nations.

The funding available for each initiative was only (US) $1-3,000. But the community organizations chose what to do with the support – for instance constructing water supply systems, drains, all-weather roads or paths, sea walls (as in the above photo) or playgrounds. In most of these cities, several community initiatives were supported and those involved came together to discuss with their local government how to expand such initiatives. They often set up jointly managed city funds to do so. Through this process, many community organizations developed new relationships with local government staff. Community organizations became the drivers of change within their settlement and within the city. These were not climate change adaptation programmes, but by allowing those in informal settlements to determine what was done, it meant hundreds of initiatives which reduce climate change risks. In many cities, communities chose to repay the funds so other community initiatives could be supported.

2: Urban dwellers as local risk analysts, managers and reducers

The billion urban dwellers who live in informal settlements are among those most at risk from climate change. They also have knowledge and capacity to identify and reduce those risks. In over 30 nations, there are national federations or networks of ‘slum’/shack/homeless people. The foundations of these federations are savings groups, mostly formed and managed by women. Joel Bolnick fromSlum/Shack Dwellers International/SDI highlighted how these savings groups are also risk analysts, managers and reducers. Indeed the reason why the savings groups were set up was to help very low-income women manage risk and increase their resilience to shocks, including sudden and extreme weather events that can damage their homes and livelihoods. They build this resilience by creating savings accounts and having quick and easy access to loans when needed. These savings groups have supported many initiatives – building or improving homes, building and managing community toilets and washing facilities, and carrying out censuses in informal settlements to generate the data needed to design and implement upgrading schemes.

Siku Nkhoma from the Centre for Community Organisation and Development gave examples of how the 50,000 members of the Malawi Homeless People’s Federation had negotiated for land, built homes and constructed 2,500 eco-friendly toilets in different urban centres.

3: Partnerships between slum dweller groups and city governments can build resilience at the city scale

Alice Balbo from Local Governments for Sustainability – ICLEI emphasized that where local governments have learnt to work with those living in informal settlements, we begin to see a model of climate change adaptation that is centred on those most at risk and capable of helping the city scale-up its efforts. These partnerships draw on household, community and local government resources, and thus require far less external funding than conventional climate change adaptation plans. In over 100 cities, slum/shack dweller federations have memorandums of understanding with city governments to formalize these partnerships. In many cities, there are City Funds jointly managed by local governments and community organizations

4: International and national funds should be funding local processes, not projects

In the few city initiatives that have supported climate change adaptation, this generally starts with a city vulnerability study, then with experts identifying projects, then measures proposed to seek funding. The ACCA programme described above does this the other way round – providing funding, letting those on the ground make decisions and in doing so act on risk and vulnerability. Instead of a national fund to which local governments apply, each urban centre should be allocated funds whose use has to be determined with community organizations with transparency in how funding priorities are determined and supported.

The Community Organizations Development Institute (CODI) in Thailand shows how a national government fund can support community organizations formed by people living in informal settlements to design, manage and fund their own upgrading programme or housing initiative. This makes CODI funding go so much further. Since much of this work is funded by loans, it also means funds that are returned go to benefit other communities. If governments shifted from funding projects to funding the community processes outlined above, the scale of what they could achieve would be enormously increased. These community organizations often leverage increased support from local governments and businesses, as shown by CODI, by ACCA, and by the initiatives of the slum/shack dweller federations.

5: Climate change adaptation and good local development go hand in hand

Steve Hammer from the World Bank emphasized how climate change adaptation has to be treated as a co-benefit of development initiatives. None of the initiatives mentioned above were designed as climate change adaptation. But, by addressing priorities identified by community organizations from informal settlements, many risks were reduced as housing was improved, infrastructure installed (for water, sanitation and drainage) and services provided (including disaster risk response capacities). Without this, there will be little buy-in to climate change adaptation from the community groups and local governments. And without their buy-in and collaboration, there is little hope of progress.

6: The five points above help build the financial, institutional and political base that climate change adaptation needs in every urban centre

As local processes help build local governments with more capacity, transparency and willingness to work with those in informal settlements, it also means local governments that can better use international funding to complement local resources, and international agencies can work with them more effectively.

7. The big international climate funds need to work with local governments and informal settlement residents

Funds that support local processes have produced new insights into what funding is needed and by whom – but this presents enormous institutional challenges to any national or international fund set up to support climate change adaptation. Their bureaucracy could never manage support for thousands of low-cost initiatives to community organizations.

At the moment, much of the discussion on adaptation financing is around the confusion caused by the different international funds and their funding procedures, the limited funding these have (because of the lack of commitments by many governments) – and for many, the surprisingly low amount of funding actually committed.

But what is more at issue is the incapacity of these funds to support and work with the kinds of local and city processes that can and should drive climate change adaptation. Why isn’t there more discussion of this? Why are the two most important groups for climate change adaptation (and for development) so marginalized in these discussions – local governments and representative organizations of the billion people living in informal settlements? What is the point of developing new international funds if they cannot work with those who will make best use of this funding?

Some of these international funds don’t want their support for adaptation to include development. So they won’t fund the infrastructure that so many cities lack, only the increase in the infrastructure’s resilience to climate change impacts. But you cannot increase the resilience of infrastructure that is not there. Financing adaptive capacity in cities is not just funding the incremental improvements to cope with increased risk – it is building the institutional, financial and political capacity to act, invest and govern well.

8: Support for local processes needs 1 per cent of aid

If funds to support the local processes outlined above got 1 per cent of aid, this would mean US$1.2 billion a year. Imagine the impact these funds could have if applied to the slum/shack dweller federations and to ACCA.

Slum/Shack Dwellers International (SDI) has supported the growth and consolidation of federations of slum/shack/homeless people in over 30 nations, supporting the creation of 16,000 savings groups, securing tenure for 200,000+ households and providing hundreds of thousands with better access to toilets and washing facilities. There are memoranda of understanding with more than 100 cities, censuses of 4,200 informal settlements (and profiles and maps covering many more than this). All this with (US) $30 million external funding. With$600 million a year, what more could they achieve? 2,000 cities with strong federation-city government partnerships? Much improved provision for sanitation and washing for hundreds of millions?

With around $10 million, 2009-2012, ACCA supported 1,000 community initiatives, 150+ cities with discussions between community organizations and local governments and over 100 City Funds. With US$600 million, this could support 60,000 community initiatives, 9,000 cities with discussions between community organizations and over 6,000 City Funds. The achievements of ACCA and of SDI are in the collective achievements of the hundreds or thousands of groups they support, to whom they give choice, voice and influence. These are the kinds of transnational networks that can help channel support direct to action on the ground.

Of course, there are other key issues for financing urban climate adaptation. Perhaps the most important is how to get adaptation, resilience and mitigation built into the vast private investment flows that are the key drivers of urbanization. As Jeb Brugmann pointed out, the investments needed to achieve resilient and low-carbon urban centres are far beyond what the climate change adaption funds are likely to have.

But at least we have a working model for what has long seemed an impossible task – building resilience to climate change among those with the lowest incomes and least political power. We can see the scale and scope of what external funding could support – and the relatively modest funding that this would require.

iied – International Institute for Environment and Development

The sea-wall built by members of the Philippines Homeless People’s Federation in Davao with a loan from the the Asian Coalition for Community Action. The loan encouraged the government to extend the wall further. Credit: ACHR

The sea-wall built by members of the Philippines Homeless People’s Federation in Davao with a loan from the the Asian Coalition for Community Action. The loan encouraged the government to extend the wall further. Credit: ACHR