Africa – Americas – Arab States – Asia & Pacific – Central Asia – Europe

UN Habitat will Adopt, commit, implement, encourage, promote adequate investments, support, recognize, invite, underscore and promote urban disaster response;

Urban climatic disaster response – #Disasterlaw

From All cities implementing policies endorsing Urban Climatic Emergency Evacuation Plan (#UCEEP) initiative to What is the military’s role in the New Urban Agenda?

Disaster law initiatives to combat climate change

“Duty-to-protect”

Drawing the state of disaster action around the world

“Duty-to-warn”

Participatory meetings to get to concrete catastrophe risk insurance solutions

“Duty-to-prevent”

Increase ability to have national drr assessment strategies, risk assessments International cooperating and access to early warning systems and drr information and assessment that need to be deliver to all by 2030.

“Duty-to-inform”

(urban/rural) disaster law, an urgent step-up of multi-stakeholder collaboration, coalitions of non-state actors and their flagship disaster adaptation initiatives?

“Duty-to-respond”

Unsupported substantial self-settlements without assistance shelter permanent shanti towns

“Duty-to-shelter”

Their objectives are to stay mobilized, accelerate climate action and streamline the implementation of the Paris Agreement, the Agenda for Action.

“Strengthening concrete action to bridge the gap between current commitments and the objective of emergency in the Paris Agreement”.

RE: Resolution 71/235, 71/256, Draft-Outcome-Document-of-Habitat-III-E

We take full account of the milestone achievements of the year 2015, in particular the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, including the Sustainable Development Goals, the Addis Ababa Action Agenda of the third International Conference on Financing for Development, the Paris

Agreement adopted under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction for the period 2015–2030, the Vienna Programme of Action for Landlocked Developing Countries for the Decade 2014–2024, the Small Island Developing States Accelerated Modalities of Action Pathway and the Istanbul Programme of Action for the Least Developed Countries for the Decade 2011–2020. We also take account of the Rio Declaration on

Environment and Development, the World Summit on Sustainable Development, the World Summit for Social Development, the Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development, the Beijing Platform for Action, the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development and the follow-up to these conferences.

Adopt and implement disaster risk reduction and management, reduce vulnerability, build resilience and responsiveness to natural and human-made hazards, and foster mitigation of and adaptation to climate change;

We aim to achieve cities and human settlements where all persons are able to enjoy equal rights and opportunities, as well as their fundamental freedoms, guided by the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations, including full respect for international law. In this regard, the New Urban Agenda is grounded in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, international human rights treaties, the Millennium Declaration and the 2005 World Summit Outcome. It is informed by other instruments such as the Declaration on the Right to Development.

Ensure environmental sustainability, by promoting clean energy and sustainable use of land and resources in urban development; by protecting ecosystems and biodiversity, including adopting healthy lifestyles in harmony with nature; by promoting sustainable consumption and production patterns; by building urban resilience; by reducing disaster risks; and by mitigating and adapting to climate change.

We acknowledge that in implementing the New Urban Agenda particular attention should be given to addressing the unique and emerging urban development challenges facing all countries, in particular developing countries, including African countries, least developed countries, landlocked developing countries and small island developing States, as well as the specific challenges facing middle-income countries. Special attention should also be given to countries in situations of conflict,

as well as countries and territories under foreign occupation, post-conflict countries, and countries affected by natural and human-made disasters.

We commit ourselves to strengthening the coordination role of national, subnational and local governments, as appropriate, and their collaboration with other public entities and non-governmental organizations in the provision of social and basic services for all, including generating investments in communities that are most vulnerable to disasters and those affected by recurrent and protracted humanitarian crises. We further commit ourselves to promoting adequate services, accommodation and opportunities for decent and productive work for crisis-affected persons in urban settings, and to working with local communities and local governments to identify opportunities for engaging and developing local, durable and dignified solutions while ensuring that aid also flows to affected persons and host communities to prevent regression of their development.

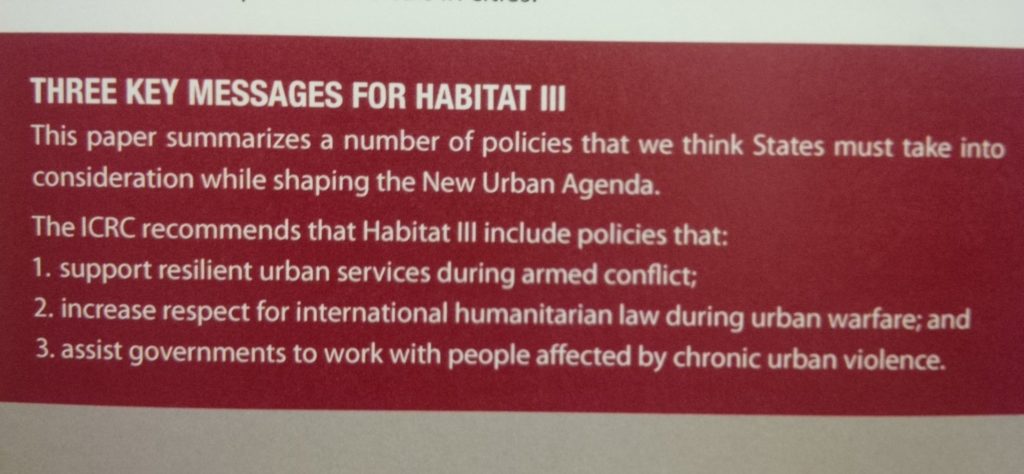

We acknowledge the need for governments and civil society to further support resilient urban services during armed conflicts. We also acknowledge the need to reaffirm full respect for international humanitarian law.

We recognize that cities and human settlements face unprecedented threats from unsustainable consumption and production patterns, loss of biodiversity, pressure on ecosystems, pollution, natural and human-made disasters, and climate change and its related risks, undermining the efforts to end poverty in all its forms and dimensions and to achieve sustainable development. Given cities’ demographic trends and their central role in the global economy, in the mitigation and adaptation efforts related to climate change, and in the use of resources and ecosystems, the way they are planned, financed, developed, built, governed and managed has a direct impact on sustainability and resilience well beyond urban boundaries.

We also recognize that urban centres worldwide, especially in developing countries, often have characteristics that make them and their inhabitants especially vulnerable to the adverse impacts of climate change and other natural and human-made hazards, including earthquakes, extreme weather events, flooding, subsidence, storms – including dust and sand storms – heat waves, water scarcity, droughts, water and air pollution, vector-borne diseases, and sea-level rise particularly affecting coastal areas, delta regions and small island developing States, among others.

We commit ourselves to facilitating the sustainable management of natural resources in cities and human settlements in a manner that protects and improves the urban ecosystem and environmental

services, reduces greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution, and promotes disaster risk reduction and management, by supporting the development of disaster risk reduction strategies and periodical

assessments of disaster risk caused by natural and human-made hazards, including standards for risk levels, while fostering sustainable economic development and protecting all persons’ well-being and quality of life through environmentally sound urban and territorial planning, infrastructure and basic services.

We commit ourselves to promoting the creation and maintenance of well-connected and well-distributed networks of open, multi-purpose, safe, inclusive, accessible, green, and quality public spaces; to improving the resilience of cities to disasters and climate change, including floods, drought risks and heat waves; to improving food security and nutrition, physical and mental health, and household and ambient air quality; to reducing noise and promoting attractive and liveable cities, human settlements and urban landscapes, and to prioritizing the conservation of endemic species.

We commit ourselves to strengthening the sustainable management of resources, including land, water (oceans, seas and freshwater), energy, materials, forests and food, with particular attention to the environmentally sound management and minimization of all waste, hazardous chemicals, including air and short-lived climate pollutants, greenhouse gases and noise, and in a way that considers urban–rural linkages, functional supply and value chains vis à vis environmental impact and sustainability, and that strives to transition to a circular economy while facilitating ecosystem conservation, regeneration, restoration and resilience in the face of new and emerging challenges.

We commit ourselves to strengthening the resilience of cities and human settlements, including through the development of quality infrastructure and spatial planning, by adopting and implementing integrated, age- and gender-responsive policies and plans and ecosystem-based approaches in line with the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction for the period 2015–2030; and by mainstreaming holistic and data-informed disaster risk reduction and management at all levels to reduce vulnerabilities and risk, especially in risk-prone areas of formal and informal settlements, including slums, and to enable households, communities, institutions and services to prepare for, respond to, adapt to and rapidly recover from the effects of hazards, including shocks or latent stresses. We will promote the development of infrastructure that is resilient and resource efficient and will reduce the risks and impact of disasters, including the rehabilitation and upgrading of slums and informal settlements. We will also promote measures for strengthening and retrofitting all risky housing stock, including in slums and informal settlements, to make it resilient to disasters in coordination with local authorities and stakeholders.

We commit ourselves to supporting moving from reactive to more proactive risk-based, all-hazards and all-of-society approaches, such as raising public awareness of risks and promoting ex-ante investments to prevent risks and build resilience, while also ensuring timely and effective local responses to address the immediate needs of inhabitants affected by natural and human-made disasters and conflicts. This should include the integration of the “build back better” principles into the post disaster recovery process to integrate resilience-building, environmental and spatial.

We strongly urge States to refrain from promulgating and applying any unilateral economic, financial or trade measures not in accordance with international law and the Charter of the United Nations that impede the full achievement of economic and social development, particularly in

developing countries.

We will integrate disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation and mitigation considerations and measures into age- and gender-responsive urban and territorial development and planning processes, including greenhouse gas emissions, resilience-based and climate-effective design of spaces, buildings and constructions, services and infrastructure, and nature-based solutions. We will promote cooperation and coordination across sectors, as well as build the capacities of local authorities to develop and implement disaster risk reduction and response plans, such as risk assessments concerning the location of current and future public facilities, and to formulate adequate contingency and evacuation procedures.

We will consider increased allocations of financial and human resources, as appropriate, for the upgrading and, to the extent possible, prevention of slums and informal settlements in the allocation of financial and human resources with strategies that go beyond physical and environmental improvements to ensure that slums and informal settlements are integrated into the social, economic, cultural and political dimensions of cities. These strategies should include, as applicable, access to sustainable, adequate, safe and affordable housing, basic and social services, and safe, inclusive, accessible, green and quality public spaces, and they should promote security of tenure and its regularization, as well as measures for conflict prevention and mediation.

We will promote the development of adequate and enforceable regulations in the housing sector, including, as applicable, resilient building codes, standards, development permits, land use by-laws and ordinances, and planning regulations; combating and preventing speculation, displacement, homelessness and arbitrary forced evictions; and ensuring sustainability, quality, affordability, health, safety, accessibility, energy and resource efficiency, and resilience. We will also promote differentiated analysis of housing supply and demand based on high-quality, timely and reliable disaggregated data at the national, subnational and local levels, considering specific social, economic, environmental and cultural dimensions.

We will promote adequate investments in protective, accessible and sustainable infrastructure and service provision systems for water, sanitation and hygiene, sewage, solid waste management, urban drainage, reduction of air pollution and stormwater management, in order to improve safety in the event of water-related disasters; improve health; ensure universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all, as well as access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all; and end open defecation, with special attention to the needs and safety of women and girls and those in vulnerable situations. We will seek to ensure that this infrastructure is climate resilient and forms part of integrated urban and territorial development plans, including housing and mobility, among others, and is implemented in a participatory manner, considering, innovative, resource-efficient, accessible, context-specific and culturally sensitive sustainable solutions.

We will support decentralized decision-making on waste disposal to promote universal access to sustainable waste management systems. We will support the promotion of extended producer responsibility schemes that include waste generators and producers in the financing of urban waste management systems, that reduce the hazards and socio economic impacts of waste streams and increase recycling rates through better product design.

We will promote the integration of food security and the nutritional needs of urban residents, particularly the urban poor, in urban and territorial planning, in order to end hunger and malnutrition. We will promote coordination of sustainable food security and agriculture policies across urban, peri-urban and rural areas to facilitate the production, storage, transport and marketing of food to consumers in adequate and affordable ways in order to reduce food losses and prevent and reuse food waste. We will further promote the coordination of food policies with energy, water, health, transport and waste policies, maintain the genetic diversity of seeds and reduce the use of hazardous chemicals, and implement other policies in urban areas to maximize efficiencies and minimize waste.

We will explore and develop feasible solutions for climate and disaster risks in cities and human settlements, including through collaborating with insurance and reinsurance institutions and other relevant actors, with regard to investments in urban and metropolitan infrastructure, buildings and other urban assets, as well as for local populations to secure their shelter and economic needs.

We reaffirm the role and expertise of UN-Habitat, within its mandate, as a focal point for sustainable urbanization and human settlements, in collaboration with other United Nations system entities, recognizing the linkages between sustainable urbanization and, inter alia, sustainable

development, disaster risk reduction and climate change.

Source: HABITAT III NEW URBAN AGENDA Draft outcome document for adoption in Quito, October 2016