March 4, 2015 —  Editor’s note: 2015 is shaping up to be a pivotal year with respect to climate change as growing concern about impacts converges with a critical stage in the decades-long process of shaping an international agreement to change our trajectory. To help us all prepare for the potentially game-changing 21st gathering of the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP 21) in Paris beginning Nov. 30, by reporter Fiona Harvey. This first installment answers some basic questions about the U.N. talks.

Editor’s note: 2015 is shaping up to be a pivotal year with respect to climate change as growing concern about impacts converges with a critical stage in the decades-long process of shaping an international agreement to change our trajectory. To help us all prepare for the potentially game-changing 21st gathering of the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP 21) in Paris beginning Nov. 30, by reporter Fiona Harvey. This first installment answers some basic questions about the U.N. talks.

Why 2015 could be the most important year ever for curbing climate change

Climate change negotiations seem to crawl along interminably at the pace of the glaciers they are meant to protect, with little perceptible progress as meeting follows meeting and conference follows lackluster conference. But this year we are seeing remarkable momentum building toward a historic conference in Paris in the closing days of 2015, by the end of which we will either have a new international agreement on cutting greenhouse gas emissions, or we will have seen the last of truly global efforts to strike a deal on saving our planet.

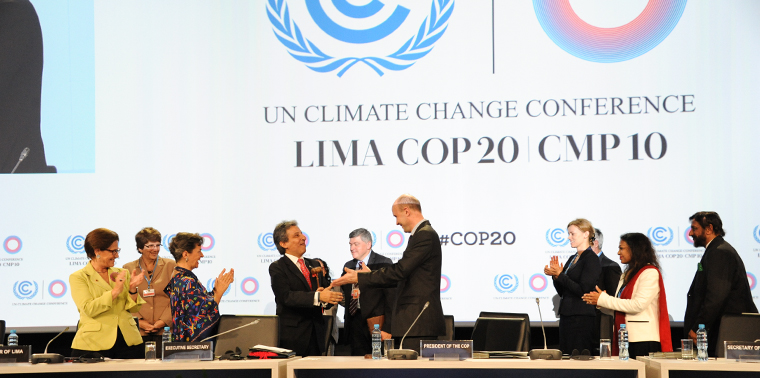

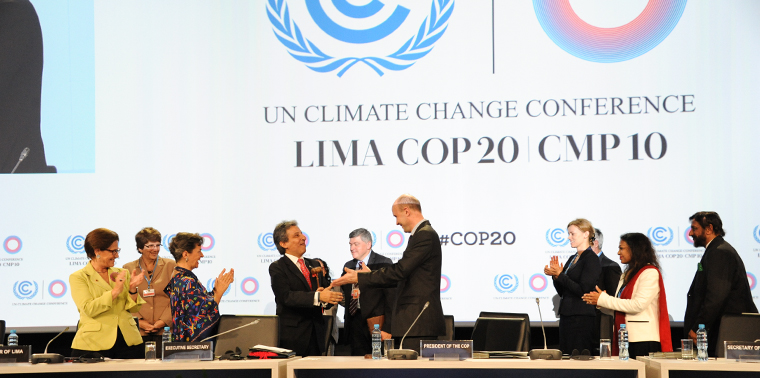

We began the year with the outcome of Lima, last December’s United Nations gathering at which delegates drafted the outline of such an agreement that would come into force starting in 2020. That in turn followed a landmark deal between the U.S. and China in November to set limits on their greenhouse gas output. By the end of spring, all of the world’s major economies should be coming up with similar plans. Then, after some months of considering these proposals, and as 2015 ends, Paris will host COP 21 — the most important meeting on global warming since the Copenhagen talks six years earlier. What is decided there will determine the future of Earth’s climate for decades to come.

What is supposed to happen in Paris?

Governments will meet for two weeks to hammer out a new global agreement that will establish targets for bringing down global greenhouse gas emissions after 2020. Both developed and developing countries are expected to bring stringent goals to the table: absolute cuts in greenhouse gas emissions for industrialized countries, and curbs or relative reductions — such as cuts in CO2 produced per unit of GDP — in the case of poorer nations.

Why after 2020?

The world’s major economies, and many smaller ones, already have agreed on targets on their emissions up to 2020. These were settled at the Copenhagen climate summit in 2009, which marked the first time both developed and developing countries had agreed on such aims at the U.N. But that meeting was overshadowed by scenes of chaos and bitter fighting, so the 2020 targets — while still valid — could not at that time take the form of a full international and legally binding pact. The hope is that Paris will see less discord and a more constructive approach to continuing action on emissions to 2030 and beyond.

What is at stake?

With the publication of the fifth report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in 2013–14, we know more about the science of climate change than ever before, and what we know is troubling. The research embodied in that report put it beyond doubt that the climate is changing under human influence, and warned of the dire consequences — in the form of widespread droughts, floods, heat waves and other weather extremes — if greenhouse gases are left unchecked.

What is also at stake is the future of international action on global warming. As the Copenhagen summit showed, there are deep rifts among leading countries and among populous blocs over what action should be taken, by whom and how quickly, and how to pay for it.

The U.N. process of negotiations on a global accord has been going on for more than 20 years, since the first IPCC report in 1990 summed up our knowledge of climate science and concluded the world should be seriously concerned. That led to the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change, signed by virtually all countries in 1992 and committing them to make efforts toward “preventing dangerous anthropogenic interference with Earth’s climate system” without specifying what or how much they should do. The Kyoto protocol of 1997 was intended to flesh out those preventive actions by stipulating cuts in emissions from industrialized nations, but that collapsed when the U.S. Congress refused to ratify the protocol because it did not impose emissions targets on developing countries such as China. There followed years of stagnation in the talks, until at Copenhagen in 2009 major developed and developing economies agreed jointly for the first time to cut their emissions or curb their rise, respectively.

After the damage done at Copenhagen, the talks limped on. But the process is fragile. If Paris witnesses scenes of discord and high drama anything like those of 2009, and if there is no clear outcome, it is hard to see that faith in the U.N.’s ability to hold nations together on this issue could survive.

What should governments agree on?

They should agree on post-2020 emissions targets for all the leading economies, and less stringent actions on emissions for all nations. Three of the leading players have already set out their intended emissions targets, which bodes well for the outcome of Paris. The European Union has pledged to cut its greenhouse gas emissions by 40 percent, compared with 1990 levels, by 2030. By 2025, the U.S. will cut by 26 to 28 percent, compared with 2005 levels. And China will ensure that its emissions peak by no later than 2030.

Will these targets be enough?

No. After nations have submitted their proposals for cuts or curbs, due to the U.N. in April, the plans will be subject to close scrutiny for several months to give all countries a chance to judge them. There is a degree of gamesmanship here: No country wants to pledge too much too soon, lest it give away a competitive advantage. The results of the scrutiny will be a key part of the talks in Paris and could be a stumbling block to agreement.

This all sounds depressingly familiar. Haven’t we been here before with Copenhagen?

There are some reasons to be cheerful. Copenhagen did produce an agreement, though not in the full legal form many countries would have liked. Officially, at least, the world is committed to meeting those aims by 2020. So if Paris produces a fresh agreement lasting into the 2020s, it is a step forward.

What legal form will an agreement take?

We don’t yet know. There are three main options on the table, laid out at the U.N. conference in Durban in 2011 at which it was agreed that the Paris meeting should take place: “a protocol, another legal instrument, or an agreed outcome with legal force under the convention applicable to all parties.” The third is the most likely.

What does that mean?

We don’t quite know that, either. Some countries take it to mean that any targets agreed at Paris will be legally binding on the countries adopting them, so countries could be subject to international penalties if they are not met. Others argue that the framework agreement — a core agreement setting out the principle that countries must take on post-2020 targets — could be legally binding at an international level, while the targets themselves would be recorded separately and so not strictly binding under law.

The question of the legal form of an agreement has been a vexed one at these talks, and has a checkered history. The Kyoto Protocol of 1997 was fully legally binding under the foundation treaty, the UNFCCC, and signed by the U.S. and nearly every other country. But that meant nothing in practice when the U.S. Congress immediately refused to ratify it and left the protocol in limbo. Other nations that did ratify later reneged on their commitments. None has suffered any sanctions as a result.

Copenhagen’s “political declaration,” outlining the pledges on emissions made by the world’s biggest economies, had to be relegated to an unofficial appendix in the legal outcome of that summit, and so was derided by some. But, though technically it had less legal force than Kyoto, it is at least still in place six years later and countries are still committed to meeting those pledges by 2020. It also forms the basis of the Paris talks.

Paris will not produce a fully articulated treaty like the UNFCCC — there is not enough time or appetite for that — but as long as it produces a definite outcome, with all of the major parties agreeing to targets even if they are not legally enforceable in the strictest sense, then it will represent significant progress and should be enough to keep the U.N. process intact.

What if the talks collapse at Paris?

That is likely to mark the effective end of international action on the climate coordinated by the U.N.

There are divergent views on the centrality of the U.N. talks to preventing dangerous climate change. These are “top-down” talks: Governments decide at an international level how much of an emissions reduction they will contribute and draft national policies to cascade this through their economies. An alternative is the “bottom-up” strategy, which posits that businesses and civil society organizations are more effective in taking prompt action and will do so in their own interests while governments still argue over semicolons in an international treaty.

Ultimately, these two approaches are closely linked. Top-down targets can spur bottom-up actions, while successes in bottom-up projects can encourage governments to be more courageous in setting national climate strategies. The reverse is also true: Without top-down negotiations, some companies are likely to see a commercial advantage in acting as a free rider, stalling on emissions cuts and refusing to take part in bottom-up actions.

So it is likely that some element of both will be necessary. The U.N. is not the only top-down forum: the U.S. leads the Major Economies Forum, and the G7 and the G20 also discuss climate actions. But the U.N. is the only arena that draws all developed and developing countries together and gives small nations a voice to challenge the biggest.

And after Paris?

That is anybody’s guess. No sooner had President Obama, late last year, toasted his deal on emissions with the Chinese president than Republicans vowed to strike it down. Any commitment made now for action until 2025 or beyond, in any country, runs that risk.

What can go wrong?

Lots. Although China has set forth its commitment, other key developing countries — India chief among them — have yet to do so, and may stretch the deadline. The process by which countries will review each other’s targets between now and the Paris gathering is also fraught with uncertainty, and it is not clear what will happen if countries cannot agree how to judge the targets.

Another key question is over finance. Developing countries were promised at Copenhagen at least $30 billion in “fast-start financing” by 2012 to help them make the investments needed in low-carbon infrastructure and begin adapting to the effects of climate change. That promise was broadly achieved — but by 2020, those finance flows are supposed to reach $100 billion per year. Where will the money come from? Rich countries are adamant that only a minor amount will come from their taxpayers, and the rest from the private sector. Poor countries are demanding more, and not cash redirected from existing aid budgets. It may be possible to find some middle ground, but this could be a breaking point.

Paris will be a crunch conference in every sense. The fragile U.N. process could emerge resurgent if nations can come together, or it could be battered to an effective end. Either way, global emissions are likely to continue rising for years more, increasing the risk that warming will exceed the 2 C mark that scientists posit as the threshold beyond which climate change becomes irreversible. Paris will not be enough in itself to prevent that, but it could go a long way to deciding our fate.

This article originally appeared at Ensia.com.

Editor’s note: 2015 is shaping up to be a pivotal year with respect to climate change as growing concern about impacts converges with a critical stage in the decades-long process of shaping an international agreement to change our trajectory. To help us all prepare for the potentially game-changing 21st gathering of the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP 21) in Paris beginning Nov. 30, by reporter Fiona Harvey. This first installment answers some basic questions about the U.N. talks.

Editor’s note: 2015 is shaping up to be a pivotal year with respect to climate change as growing concern about impacts converges with a critical stage in the decades-long process of shaping an international agreement to change our trajectory. To help us all prepare for the potentially game-changing 21st gathering of the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP 21) in Paris beginning Nov. 30, by reporter Fiona Harvey. This first installment answers some basic questions about the U.N. talks.